For my dad, it all began with a lingering pain around his collarbone, like someone had punched him there and left a bruise just below the skin. It was the sort of feeling you wake up with the next morning after a long day of yoga or hiking after months of only sitting on your ass, only that was not how dad was. For as long as I had known him, regardless of the weather, he would throw on shorts and the same nasty pair of shoes that had taken several toenails as collateral over the years and run five miles multiple times a week.

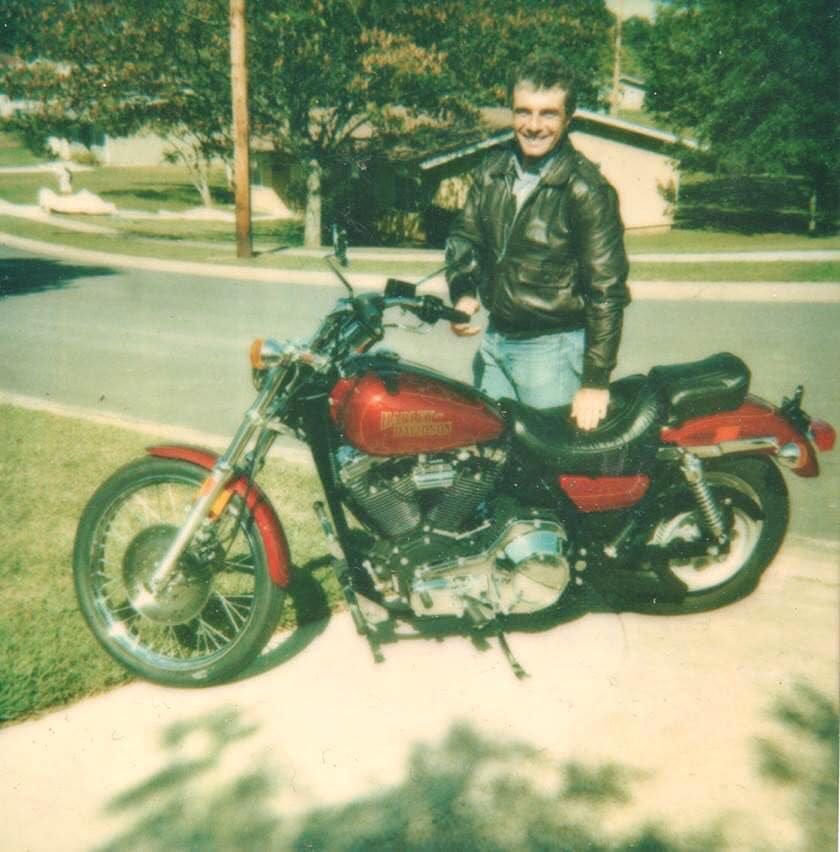

So when his sternum started throbbing uncontrollably, to the point where he couldn’t brush it off as a summer cold or too many push-ups, Dad caved in and went to his doctor. And when he didn’t like what he was told, he sought out a second opinion. And then a third. Up and down the mid-Atlantic he went, looking for someone to tell him what he wanted to hear--that he was forty-nine years old, that his eyes were blue-gray, that his cholesterol could maybe be a little bit lower, and that he definitely did not have Stage 4 lung cancer.

When he first noticed the aching in his chest, it was late spring of 2000, and he spent the next several weeks covertly going from specialist to specialist without telling anyone. Not his parents, with whom he had an admittedly strained relationship. Not his girlfriend, whom he was planning on marrying within the next year. Not my mother, whom, despite their divorce, was still his best friend and with whom he called every single day to shoot the shit. And certainly not my brother, my sister, or myself, the three of us being the absolute last to know.

I should have been tipped off that something was amiss, when, a couple weeks before my 13th birthday, he took my siblings and I on a weekend rafting trip. While Adult Me would have been delighted at the prospect, Baby Me could barely tolerate walking two blocks to the playground, let alone having to spend a few days in nature under the relentless August sun.

Moreover, my dad was not the kind of person who planned vacations in general, let alone ones that would mean having to pay for a hotel and suffer the indignity of some 23-year-old in a life-jacket telling him how to paddle a boat. Yet there we were all were, pissing and moaning about potentially dying on some small rapids in central Pennsylvania, complaining about how exhausted we were and wondering if we could fuck off to the Super 8 pool.

At some point on the journey downstream, our inflatable raft snagged itself on some rocks, catching us there as the rest of the boats in our group floated out of vision. Our bail bucket, an ancient container that looked like it held crabs or cement or plaster in a past life, was all we had to save ourselves from sinking into the Suquehannah. And as my brother, sister, and I sat there uselessly, crying over ruined lunches and clothing, there was my dad, gritting his teeth into something that looked like a smile and scooping out water. Like he was enjoying himself, despite our bickering, despite the water-logged socks, despite the knowledge that, whatever the end looked like, it was all going to come crashing down on him soon.

It was September when he broke the news to us: a week earlier to my mother and to our teachers, as a heads up, and then to his children on a wet Sunday morning. Sundays in 8th grade are already a shitty concept as-is---no thirteen-year-old on this Earth enjoys the idea that it’s only one more sleep until you're back in class, getting teased about your weight and having teachers look the other way when stress has you crying in the bathroom. On that morning, Dad had tried to soften the blow by showing up at my mom’s house with several dozen fresh donuts and by putting on his favorite records (which were, de facto, our favorite records).

I remember sitting there in utter shock, powdered sugar smeared on my face, trying to do the math in my head as he lied and told us his cancer was only at Stage 2. Stage 2 was only half-death in my little brain. Stage 2 meant that things had to get much worse before it was worth being really, truly scared. Stage 2 meant that there was hope, still a reason to smile.

I carried that hope with me for a month, as we sat and watched reruns of The Simpsons together, like we always did. Dad laughed and smiled and repeated bits like he always did---the only noticeable difference was that he seemed a little worn-out and tired, like it was just the tail-end of a bad flu. I carried that hope when my parents sent me to a support group for kids of cancer patients, as I sat surrounded by children crying because brain cancer had taken their mother or a spinal tumor had left their dad bed bound.

I carried that hope with me when, on October 29th, my mom drove us to the hospital under the guise that my dad was, by his parents words, “having a bad night”. As we all sat in the waiting room for hours, I was more concerned about the fact I still hadn’t eaten dinner or finished my homework.

By the time it was my turn to go and talk to him, however, the hope had evaporated almost instantly. There he was, intubated, jaundiced, tear-streaked and panicked. My dad, who was the one guy all the neighborhood kids wanted to push them on the swings or pull them on sleds, always grinning like a fool and trying to get a rise out of everyone in the room, was no longer smiling.

I don’t think, even in that moment, it crossed my mind that Dad was going to quietly die the following morning. Instead, I thought of him driving me to clarinet practice and quizzing me on world capitals, of us going to the dollar theater and sneaking in candy under his bulky winter coat, of our ritual goodbye consisting of the mantra “Kiss. Hug. SQUEEEEEZE!” and how that last step always left me breathless from the force of his embrace.

And so I held his hand, told him I loved him, and took my turn to smile.

Now me, I am the sort of person who will tell perfect strangers about every little ache and pain in my body, completely unprompted by anything except my own boredom.

Did you know, I say to the woman sitting next to me on the train, that sometimes my right ear canal will start throbbing moments before it starts to rain?

I once jammed a tendon in my neck backflipping off playground equipment, I opine to a bartender at an airport T.G.I.Fridays when he asks me if I want another glass of wine. I couldn’t walk for two weeks.

I was in labor for thirty hours, I lament to the Uber driver as they take me to a friend’s house. I have no shame anymore because I took a massive dump on at least three, maybe four people while they manually broke my water. Do I notice as they start turning the volume dial up on the car’s sound system? No. Jason Derulo can be crooning away as we blast down the highway and I am perfectly happy to let them know how many doctors had to gaze into the wonder that is my taint.

Over the course of the next twenty years, this need to overshare went mostly unchecked--or if it did, I decided that I wasn’t the problem. It was simply other people couldn’t handle me at my rawest. A co-worker would invite me out to drinks after work, and after two beers, you could almost smell their desperation to get away from me. I’d make what felt like an actual adult friend, and over the next few days would be crying to them over how lonely I was over Facebook, blurting out much I thought about death, how much I just wished I was hotter or smarter or less of a fuck-up. Someone would be engaged in some very casual-but-overt flirting, and it would always end with me talking about how no one could ever, truly want to be near me. I’d spend the next several years wondering how I could have ever pushed them away.

Didn’t people want honesty? Didn’t people want disclosure? Didn’t almost everyone on this Earth know that they could die at any moment and leave everyone else they ever cared about always wondering what I wondered about my dad: who really was this person and what did I mean to them?

I can’t blame this impulse solely on my dad, not even nearly--the decades of binge drinking and bulimia and record-setting low self-esteem make a wonderful bullshit side salad to accompany the trauma of a death like his. But for a long time, a longer time than I’d like to admit, oversharing was my way of coming to terms with reality that people will leave you for good. Not just in death--in failed romances, in switching careers, in once-intense friendships where one day you realize that neither of you have reached out to each in years. Sometimes out of malice or tragedy, to be sure, but more often, just from drifting down the slow and meandering curve of time.

Nearly two years ago, my daughter was born. And just as I thought I was beginning to let go of this need to control the lasting image other people have of me, of finally being ok with the fact that I went through some real fucking awful shit in 2000 and moving on, it came back like an old sickness. It was not just that paradox of grief--that as you get better, happier things get sadder in the absence of a dead loved one--that already have me in the beginning stages of bombarding her with my dad’s ghost. It was also the very palpable sense of fear and acceptance that I will one day die and hurt the person I love the most simply in the act of dying.

While I was pregnant, I was given a notebook filled with prompts for writing letters to my daughter for her to read as she grows. It was a well-meaning gift, but as I started to write the first letter, I began to feel the dreaded need to tell her every awful and wonderful thing that has happened to me over the last 33 years. To give her all of me, lest she have nothing when I’m gone. As if the friends I’ve made, the cool shit I’ve done, the work I’ve produced (sometimes regrettably weird, but hey--it’s a living), the incredibly love-filled home I’ve built with my husband, the kisses and cuddles she and I have shared would all evaporate into nothingness.

I’ve realized when you overshare out of desperation or the need to control others, it only invalidates however they might actually, organically feel about you. That it becomes less about a loving, mutual exchange of thoughts and more about wanting people to feel the pain you’ve felt because it just feels so unbearable to be that lonely in it. There is a balance between lying to save face--to not have to hurt others and confront them with truths that are necessary--and subjecting unknowing people to realities that almost destroyed you.

I will only ever partially understand why my dad lied about the extent of his illness. If I’m being honest, it still occasionally pisses me off, even after twenty years. I think of all the questions I would have asked him, all the music we would have listened to, all the photos I would have taken on my little point-and-shoot camera had I known my time was so limited. I don’t have much of him left, and with each passing year, the memories of his voice, his hugs, the way he couldn’t cook for shit but could fuck a barbecue up good and proper, feel distilled to the point of mythology. My mom tells me that my dad always said he would die young. Sometimes I wonder if it was the myth he wanted. I know that sometimes, as I was bent over a toilet and feeling my heart pound unnaturally fast, that the notion people would at least remember me if I died like that floated in the back of my head.

My dad has been dead longer than the amount of time I knew him alive by several years. Somehow, in those last few ones, with good therapy and the support of loved ones, I’ve come through the other side of my rock bottom. In two decades, his absence continues to teach more about myself in ways I still can’t predict. I’m going to screw up and inadvertently burden her with some hard history just by the nature of being human together. But I know this much--I don’t want to intentionally move through each new day like I am creating ghosts for my daughter--ephemeral beings she can only see when she squints her eyes and happens to be at the right place at the right time. I want to be honest and open, but in-the-moment. I want to live for the kiss/hug/squeeze. I want her to be able to, when I die, tell other people about the time I took her on a rafting trip so god awful that it’s now a source of profound joy and humor.

When it is my turn to go and she has cause to think of me, I want her to really, truly have a reason to smile.

This post was regretfully un-edited, so my apologies for any typos and trash. I miss you every day, Daddy. Please don’t be too hard on me, wherever you are.—Your Bubbles

I can’t believe it’s been 20 years. It’s so unfair you three lost your Dad so young. Your writing brought him to life Angie, he was so much fun. I was this 12 year old boy and he was my mischief Sherpa. The most vivid memory was intentionally accidentally beheading my sister’s chocolate Easter doll (we just meant to crack it) and Tom thinking he could fix it while both of us laughed at the horror that awaited is if my Dad found out. He was also the sage that taught me about scrotal chafing cream - guys don’t forget that (aaahhh) moment. And every time I hear the Steve Miller Band I think of him, especially him singing “hoo hoo” in Take The Money and Run. He came into my life at the perfect time and was very good to me throughout my childhood and twenties. He truly was. So many great memories. He just took over a room and you couldn’t take your eyes off him and it’s so unfair and tragic that he missed out on so much and you three kids have this empty space that will never be solved. But just know that you have a family that loves you and is so fucking proud of what you’ve done and admires the person you are.

An incredibly moving piece, I’m so sorry you had to endure such a harrowing loss so young, but I’m glad that you’ve managed to reach the point where you can write about everything you’ve experienced so eloquently and with profound insight. The stuff you & Lindsay put out always brightens my day, as I’ve never left anything you’ve touched not laughing. Your daughter has a great mom 💕